One Country, Two Systems:

Public Sector Performance and Regulatory Capture in Cyprus

12 October 2021 | Philip Ammerman

1. Introduction

On 30 May 2021, national elections were held in Cyprus to elect Parliamentary representatives. Prior to this, there was a massive outpour of dissent and dissatisfaction by voters. Undercover reporting by Al Jazeera had led to the close of the Citizenship by Investment Programme. Subsequent inquiries first on a limited sample of files, then on all passport awards, showed that widespread irregularities had occurred.

Once more, Cyprus’ reputation was being dragged through the mud. Once more, ordinary Cypriots were furious that a well-connected elite was seemingly allowed to enrich themselves at the public expense.

This followed on a number of other expensive adverse events:

-

The 2018 Cooperative Bank Liquidation saddled the public sector with at least a further € 3 billion in debt, and revealed that politicians and other public figures had not only received high, unsecured loans but had also had their debts forgiven or written down.

-

The 2013 Banking Crisis, which occurred at the beginning of President Anastasiades’ first term, was even more disastrous, causing major economic damage to the government, households and companies across the political spectrum.

-

The 2011 Mari explosion, in which confiscated Syrian munitions exploded, led to the destruction of one of Cyprus’ two conventional power plants and widespread physical damage.

It is worthwhile to note that not a single figure has been convicted of a crime in these events, which have cost the country well over € 10 billion, or half its GDP.

In the May 2021 elections, a record number of political parties and candidates participated. The election slogans of many, if not most, had to do with transparency and competence.

The elections, however, did not result in the landslide people seemed to expect. In fact, there was practically no change at all. As the official results show:

-

The ruling party, Democratic Rally, lost only one vote;

-

The Progressive Party (AKEL), which functions as the main opposition party, lost one vote;

-

The extreme right wing National Front gained two seats;

-

The Citizens Alliance and Solidarity Movement each lost votes.

The purpose of this article is to ask why, in the face of so much obvious negative performance, is there such a disconnect between the idealistic aspirations most Cypriots have for their homeland, and the actual performance seen at the state and political levels.

Along the way, I will ask some related questions:

-

How can we define Cyprus public sector performance in general, particularly in economic and fiscal terms?

-

How has COVID affected public finance in 2020 and 2021?

-

How will public sector operations and fiscal management be handled in the future, given the dependence on net service exports to the economy?

I will start with public sector fiscal dimensions.

2. Public Sector Income and Expenditure

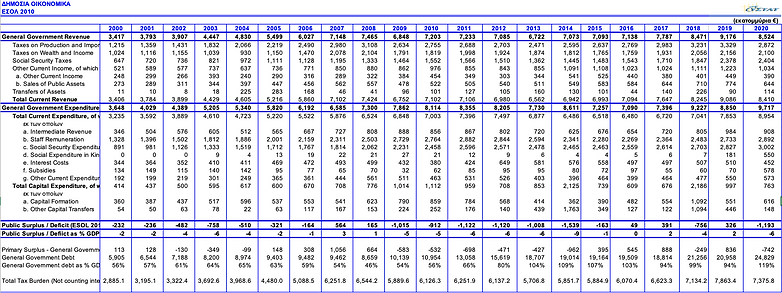

A brief review of fiscal and macroeconomic data from the past 21 years shows the following trends:

-

The role and weight of the public sector in the Cyprus economy has been growing;

-

The public sector operates at a continual deficit, exacerbated by periodic crashes, regulatory clean-ups and after-the-fact remediation;

-

The public debt is only manageable thanks to low interest rates and European Central Bank operations.

In 2000, government expenditure was € 3.65 bln in a GDP of 10.61 bln, or 34%. By 2019 (pre-COVID), this had grown to € 8.85 bln in a GDP of € 22.29 bln, or 40% of GDP.

During COVID, spending would rise still further as the government of Cyprus subsidized workers and enterprises and expanded medical spending dramatically. This is an rational response and cannot be faulted.

Figure 2 shows public expenditure as a share of GDP. In 2000, public expenditure amounted to 34% of GDP. During the Christofias Presidency, the public expenditure exceeded 40% of GDP, leading to urgent efforts during the bail-in and subsequent restructuring in 2013-2014. By 2019, the public share of GDP had reached 40% again, while in 2020 it shot up to 47% GDP due to emergency COVID spending.

The trend line is clear: public expenditure has continued to rise. This is either because of an expanding state (which appears to be the case in Cyprus) or due to GDP denominator effects, such as tax evasion by companies and individuals in Cyprus.

3. Public Sector Fiscal Balance

Between 2000 and 2020, Cyprus recorded a government surplus in only five years: in 2007, 2008, 2016, 2017 and 2019. It has had a deficit the remaining 16 years. The deficits reached over € 1 billion per year in 3 of 5 years of the Christofias Government.

The Christofias Government lasted from February 2008 to February 2013. It inherited a surplus of € 0.564 billion in 2007. In 2008, the surplus fell to € 0.165 billion. In 2009 the surplus turned into a deficit of € 1.02 billion; then € 0.91 billion in 2010; then € 1.12 billion in 2011; then € 1.12 billion in 2012. Altogether, the Christofias Government added € 4 billion in debt to Cyprus, without counting the results of the Mari explosion or the 2013 bail-in.

The results are seen clearly in Figure 4. By 2013, Cyprus debt-to-GDP reached 100%, and since then both have been expanding largely in synchronization, with debt rising rapidly in 2020 due to COVID expenditure.

Why has public expenditure risen so highly? There are five main explanations that we can identify from the data provided:

-

Because public sector employment and remuneration have been rising;

-

Because social insurance costs have been rising;

-

Because debt service costs have been rising, and are expected to rise further in the future;

-

Because the costs of mitigating external and internal crises has been rising;

-

Because Cyprus takes a statist approach to many sectors of development.

Let’s see each of these in turn.

4. Public Sector Employment & Remuneration

One of the main expenditure lines in the general government budget is public sector employment and remuneration. The public sector has traditionally been a source of political patronage in Cyprus, with political parties offering civil servant positions to their supporters. Jobs in the Cyprus public sector are widely understood to be jobs for life, and competition for them is significant.

Figure 5 shows that total public sector employment in Cyprus began to fall in 2011 (during the Christofias government), when general government employment reached 71,212 people. The cutbacks accelerated until 2015, when total employment fell to 63,584. Since then, it has been rising under the Anastasiades Government, despite the resolution of the Cooperative Bank of Cyprus. In the first 6 months of 2021, total public sector employment reached 70,478 people.

There have been various arguments in recent years about whether Cyprus needs so many municipalities. The Anastasiades government has repeatedly drawn attention to this. It is difficult to understand what constitutes an “ideal” municipality in Cyprus, given the disparity in geographies, tourism, residents, and other criteria. It is even more difficult to understand what an “efficient” municipality is.

However, we do note that in 2009, local government staff numbered 4,612 people (or 7% of general government employment). In 2020, local government staff numbered 4,095 people, or 6% of the public workforce. The problem, it would seem, is not so much at the local government level, at least in terms of staffing.

Staff remuneration in the public sector has indeed expanded. It has risen from € 1.33 billion in 2000 to € 2.89 billion in 2020. (Please note that this number may not capture the full social security costs embedded in remuneration).

However, the public sector remuneration costs per person, or as a share of GDP, remain relatively stable or declining in some years. Average public sector remuneration was € 39,068 / person in 2009, rising to € 41,725 in 2020. While high compared to equivalent average private sector salaries, it does deserves mention that a small republic exposed to risks such as Cyprus does need to remunerate its staff adequately in the public sector. While improvements could be made, these may not be the panacea that many critics imagine.

A key issue is productivity. While it is not the scope of this article to go into productivity, there are any number of sectors, ranging from education to the justice system, where it is clear that overall productivity is low.

The EU Judicial Scoreboard (2019), for example, shows that Cyprus is a laggard in terms of the total number of days needed to resolve a case. The 2018 OECD PISA score for educational outcomes ranks Cyprus among the lowest EU Member States in terms of performance, despite Cyprus teachers having among the highest salaries in the EU.

5. Cyprus Social Insurance Costs

One area of the Cyprus government budget that has been rising fast is social insurance. In 2000, social insurance expenditure was € 891 million, and was offset with € 647 million in tax revenue. By 2019 (pre-COVID), social insurance expenditure grew to € 3 billion in expenditure, offset by tax income of € 2.4 billion. The social insurance fund had a € 629 million deficit in that year.

The deficit is clearly illustrated in Figure 6 below:

In addition to the high cost of the social insurance deficit in absolute financial terms, it is also high in relative terms, as a share of GDP and of government expenditure. Figure 7 shows that the share of social insurance in total government expenditure rose from 24.4% in 2000 to 34% in 2019. As a share of GDP, it rose from 8.4% in 2000 to 13.5% in 2019.

This article should not be construed as being against social insurance spending. Every society wants its sick, retired and vulnerable population taken adequate care of. The pension component of social insurance is also highly fungible: it tends to be spent, not saved, by retirees, contributing to GDP growth.

The question is: how to fund it? Even leaving aside the massive increase in healthcare spending due to the introduction of the National Health Insurance System (GESI), and leaving aside COVID, the data show that Cyprus has expanded its social state further than its ability to fund it directly.

This leaves the social insurance funds vulnerable to potential cut-offs in supplemental government funding. And, in a society where people are living longer, and where the pension contributions of the wider public sector do not reflect their contributions, the question is how much longer will this last absent tax increases?

And tax increases are almost inevitable. Cyprus already faces international pressure to raise its corporate income tax. Given the rising costs of National Health Insurance, we suspect that social insurance contributions are set to rise still further.

We can measure the importance of social insurance and government payroll in overall government expenditure. In 2000, total expenditure on these two items was € 2.2 billion, and accounted for 61% of total Cyprus government expenditure and 21% of Cyprus GDP.

By 2019 (pre-COVID), expenditure on these items had risen to € 5.7 billion, or 65% of total government expenditure and 26% of GDP.

COVID pushed total expenditure to € 6.4 billion in 2020, accounting for 66% of government expenditure and 31% of GDP.

6. Cyprus Public Debt Service Costs

A further budget item that has been growing rapidly is debt service costs. Annual interest costs on the public debt have risen from € 344 million in 2000 to € 452 million in 2020. Total Cyprus public debt has risen from € 5.9 billion in 2000 to € 24.8 billion in 2020.

Today, the cost of interest accounts for 4.6% of Cyprus government expenditure and 2.2% of GDP. If interest costs were a department, it would be one of the most expensive departments in the Cyprus government.

Like other EU Member States, Cyprus is benefitting from very low interest rates and the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing (bond-buying) and zero interest rate policy. The effective interest rate that Cyprus pays has fallen from 5.8% in 2000 to 1.8% today.

As with the rising public payroll costs and social insurance costs, the question is how much longer this can continue. ECB assets are now over € 7 trillion, and the ECB has signalled the gradual end of quantitative easing. Although this gradual end will presumably take years, the Government should be ready for a potential upturn in interest rates.

Moreover, the Cypriot economy has tended to depend on “cash cow” operations in the past. For example, in previous economic cycles, construction and property used to account for 7-8% of GDP. With the end of the Citizenship by Investment Programme, it remains to be seen what source of tax revenue will be tapped to lower the public debt.

(One interesting fact about the Cyprus Citizenship by Investment Programme is that until the reforms introduced in 2019 by the Government of Cyprus, the direct income from the programme to the Government was actually very limited. The main benefit was harvested by developers and associated professions.)

7. Crisis Management Costs

Cyprus has gone through a series of expensive crises in the past 10 years. Each of these has had a major negative impact on public finances, which I attempt to quantify here. In each case, there has been no civil or criminal liability assessed on any individuals involved in these crises, which have been largely self-generated.

2011 Evangelos Florakis Munitions Explosion: € 2 billion

On 11 July 2011, munitions seized from a Cypriot-flagged vessel bound for Syria exploded. The munitions were seized in 2009 and stored in the open in shipping containers for 2 years. While estimates vary, the consensus is that the blast cost between € 2.0 – 2.4 billion to the Cyprus economy. This includes the costs of reconstructing the EAC Mari Power Plant; strengthening capacity at other power plants; and related damage to infrastructure as well as lost electricity generation capacity.

The fact that Cypriot officials allowed the munitions to be stored under extreme heat conditions, and that military officers had warned of the danger of this, reveals the quality of public sector decision-making at this time. Not a single person has been convicted as a result of this event.

2010 Greek Debt Crisis / 2013 Cyprus Banking Crisis & Bail-in: € 7 billion

In 2010, the Greek financial crisis began, leading to a nominal haircut on Greek government bonds held by Cyprus financial institutions in 2012. The damage done to Cypriot banking institutions was extensive, as the three systemic banks in Cyprus all held Greek Government Bonds to various degrees.

In 2013, the Government of Cyprus was forced to ask for a € 10 billion loan from the European Union Euro member states, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The amount requested eventually grew to a nominal value of over € 23 billion, which was higher than Cyprus’ GDP at the time.

A condition of this loan was a depositor bail-in and the liquidation of the Popular Bank of Cyprus. Credit controls were also imposed as a result.

It is impossible to know the total costs of this related event. If one takes the write-down on Greek government bonds; the liquidation costs (direct and indirect) of the Popular Bank, and the impact on the wider economy, it is likely that the total direct costs to the public budget exceed € 7 billion, considering the costs of higher debt service, unemployment and related social spending and subsidies between 2013 and the present day.

Please note that this does not take into account the value of deposits seized or liquidated.

The fact that both the Bank of Cyprus and the Popular Bank not only kept buying Greek Government Bonds after 2010, but raised their exposure to a point where even a minimum impairment would eliminate their Tier 1 capital, is incomprehensible.

2018 Cyprus Cooperative Bank Liquidation: € 3.5 billion

In 2018, the Cooperative Bank of Cyprus was liquidated after decades of mismanagement led to a vast non-performing loan portfolio. It was later found that numerous politicians were beneficiaries of NPLs that were written off.

So far, the direct costs of the resolution are estimated by the Cyprus government itself (in Cystat public accounts budget notes) at € 3.4 billion. This does not, however, include the long-term costs of servicing these and additional government bonds issued for the transaction, nor the pension costs for current and already-retired Cooperative Bank employees.

I believe that the long-term costs will easily be more than € 3.5 billion, but for the sake of a conservative forecast provide this number as an estimate.

As before, not a single person has been convicted for breach of trust of fiduciary duties or any other financial crime.

COVID-19 Pandemic

These three crises mentioned previously are quite different from the COVID crisis, which was truly a Black Swan event. The three previous crises were entirely “man-made” in that they resulted from decisions made by authorized decision-makers in the Cypriot government and/or financial sector. Moreover, those that involved financial decisions were widely ignored by the financial authorities, such as the Central Bank of Cyprus, whose mandate it is to prevent exactly this kind of situation from emerging.

It is impossible to tell how much the Cyprus Government has spent to date, but I note that government debt rose from € 20.9 billion in 2019 to € 24.8 billion in 2020, an increase of € 3.9 billion.

8. Statism in Cyprus

The final reason that the debt continues to grow is that Cyprus remains wedded to a vision of state-led development. This is seen in the continued operations and market share of public or public-private monopolies on vast sections of the economy:

-

The state-owned Electricity Authority of Cyprus remains a monopolistic energy generator in Cyprus (legislation was recently passed to partially end this status, but it has not yet been implemented).

-

The largest telecoms company, CYTA, remains partially state-owned.

-

The only two operating airports in Cyprus were both licensed to the same operator, handing it an effective monopoly with state authorisation. For an island and a country dependent on tourism, this is a remarkable oversight that violates basic principles of competition policy.

-

The major port, Limassol, was privatised while the second major port, Larnaca, remains under state control.

-

Garbage disposal remains regulated by the public sector but with collection networks operated by private collection companies. No recycling system is in place.

-

The National Healthcare System has effectively nationalized healthcare with no option for an opt-out by citizens: social insurance contributions are mandatory for citizens and employers.

-

European Union funds are now being increasingly absorbed through public-led partnerships, many of them of questionable operational or expert competence.

-

The government continues to expand its payroll and to create new “Deputy Ministries” and authorities at a rapid pace.

I am not arguing that the state is more or less effective than the private sector at managing the economy. I do note that Cyprus’ history is littered with expensive state-owned company failures, of which Cyprus Airways and the Cooperate Bank are just two recent examples.

I am arguing that the cost of state operations—and mistakes—are being borne by the citizens and private sector of the country, without any seeming responsibility on the part of the state or the individual decision-makers who oversaw the errors in the first place.

Moreover, it appears that there is a positive feedback loop between the state and its citizens precisely due to the conditions of state employment. The public appears to forgive political parties of egregious self-inflicted errors and mis-steps, as long as the public sector machine is open for business.

I don’t know how else to describe the relationship between the political outrage seen early this year, and the Parliamentary results in May 2021.

9. What’s Next?

Cyprus finds itself at a critical moment in its development. The COVID Pandemic has resulted in 2 “lost years” of development. During this time, the impact of public health measures have caused grave damage to the economy of Cyprus. The government has done the best it could under highly uncertain circumstances. The outcome, however, is high public debt and continuing uncertainty over what 2022 will bring.

Besides the preference for responsibility-free statism discussed here, other factors weigh on future economic development in Cyprus:

-

Tourism Competitiveness: It is imperative that Cyprus finds ways to improve the competitiveness of its tourism sector. Tourism accounts for at least 20% of GDP, but the tourism product is rapidly losing in relative terms of price/quality ratio against other destinations. Many of the statism factors expressed—such as high hotel operating costs (in no small part due to high electricity charges and taxes) and high transport costs (due to limited flight availability and high landing charges)—are a leading factor in declining competitiveness. It is urgent that a public-private cooperation develop a real and rational strategy for improving competitiveness.

-

International Business Competitiveness: Cyprus is becoming less competitive as a business destination. This is due not only to rising taxation and Cyprus substance compliance costs, but also due to rising property and staff costs, sub-standard and expensive telecom charges, a slow and paper-based public sector, a decrepit judicial sector and a totally dysfunctional banking sector. These factors are usually not understood by foreign investors until it is too late. The tax and property price brackets are also closing. In 2016, for example, a comparison between locating a business in Limassol versus London was compelling. In 2021, it is much less compelling. Many companies that have relocated to Cyprus in the past are now moving operations to other countries for this reason.

-

Government Operations: The quality of government operations for the average foreign investor or resident are becoming prohibitive. e-Government has been promised but never delivered. Getting government certificates is an expensive and paper-based process. Lawyers and accountants act as monopolistic rentiers, charging high fees for very average service performance, with full government approval. As any foreigner who has gone through Immigration can attest, the system is archaic and decrepit.

-

Banking Operations: Banks have become reporting extensions of the Cyprus state, especially for foreigners. If banks made loans as frequently as they conducted due diligence operations, they might have far higher profitability. Instead, it’s all about legal compliance and due diligence, often implemented twice per year for foreign residents of Cyprus. Cyprus banking fees are rising every year, adding insult to injury.

-

Legal System: The legal system continues to be see cases resolved at a very slow rate and in some high profile cases with an apparent double standard for Cypriots versus foreigners. It is imperative that Cyprus cleans up and modernizes its judicial system if it wants to remain an international business centre.

-

Russian-Cyprus Business Nexus: Changes to the Russian-Cyprus double tax treaty and other changes, particularly in banking compliance, mean that Cyprus is losing its attractiveness in what was its main investment source market.

-

Boom-Bust Cycle: Cyprus has regrettably permitted a boom-bust cycle to take hold. This was seen in the past through the banking-property cycle that crashed in 2008-2013, leading to the Bail In. It recently modified this with the Citizenship by Investment Programme, which had to be cancelled after media and subsequent government reports on irregularities. This has left developers with expensive, unfinished properties on their books, almost turning the clock back to 2013.

-

Quality of Life: The quality of life, particularly in urban areas, continues to deteriorate. There are major problems with cleanliness and garbage. There is a lack of basic coordination between municipalities in terms of public transport, parking, etc. The costs of housing continue to rise, usually for sub-standard housing quality. School places are limited and expensive, especially for foreigners who do not want to send their children to public schools.

-

Turkey: Repeated events since the 2004 Referendum and EU Accession have shown Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot community that “Independence” is probably the only solution to the Cyprus Problem. That, at least, is something that representatives in both areas are now claiming. We should also not forget that Turkey has, for better or worse, significant influence on both the European refugee issue and natural gas drilling in the Eastern Mediterranean. It is difficult to see relations improving to the point of a solution at any level. This indicates, at least to me, that geopolitical instability in the Eastern Mediterranean cannot be taken for granted. It is remarkable how few companies or officials appear to take this into account in their planning or budgeting.

-

EU Funding and the Green Transition: A large share of the European Union's Pandemic Response funds and the next 7-year budget are dedicated to the green transition and digital transformation. It is hoped that this funding could provide the momentum to achieve real change in both areas. Unfortunately, the lack of substantial national strategies in each area (driving down to the municipal sector), and the lack of a national consensus on the measures that would be needed to achieve them, hamper their effectiveness.

These negative factors are offset by some impressive achievements:

-

The tertiary education sector continues to attract foreign students and expand in terms of quality. This is an excellent sign.

-

The Limassol Casino is expected to begin operating in 2022 or soon thereafter. This will transform the tourism landscape of Cyprus and may generate significant income for the government.

-

Other investments, such as the Larnaca Port and Marina Development, the Ayia Napa Marina, various projects in Paphos and others will hopefully be completed, creating new places of employment and new poles of interest.

-

Although small in terms of assets under management, CIPA continues to attract investment funds setting up or relocating to Cyprus. Several important fintech and software companies have also established themselves here.

-

Cyprus has implemented a National Health System which, despite some obvious issues, has expanded quality healthcare to its population, in many cases using an ICT system that is extremely transparent and highly useful for patients and doctors.

We should also not overlook the fact that the two-term Anastassiades Government has been handed what one could argue is more than its fair share of challenges:

-

The Cyprus banking crisis was arguable not its fault, yet the responsibility for cleaning it up was;

-

Similarly, the Cyprus Cooperative Bank liquidation was years in the making;

-

COVID-19 has tested governments all over the world: the pandemic response in Cyprus has been measured and relatively rational. It is difficult, without hindsight, to see how this government could have done better.

These challenges should be self-evident to anyone with a passing experiential knowledge of Cyprus. These are real-world challenges that can be solved with a sustainable cooperation between public and private sector. The tremendous policy success of the tertiary education sector shows the potential that a public-private cooperation can bring in Cyprus.

And yet, to an outsider, it can appear difficult to imagine any form of lasting change. Politicians have been promising greater e-government for years now with very few results. Local monopolies in certain sector continue and are becoming more entrenched than ever. Costs are rising, and I fully expect a higher tax burden in order to cope with the social security and national healthcare deficits.

Cyprus needs leadership and consensus to make critical strategic decisions. Sadly, the Parliamentary elections and government decisions subsequent to May 2021 do not provide any indications that these strategic decisions will be made. Many of the first votes were protest votes which were not entirely constructive.

Instead, the opposite appears to be the case:

-

Ad-hoc decisions made, usually responding to media or special interest pressures;

-

No accountability for past decisions;

-

Immediate socialization of financial failures by floating new government debt;

-

No risk analysis or mitigation measures;

-

A remarkable lack of urgency on what are very critical problems.

What is also remarkable is that all these events have taken place in a broad period of peace and stability. In this time, one would have expected rising surpluses and long-term investments in productivity financed by low-cost debt.

Instead, the opposite has occurred: burgeoning public debt, mostly refinancing deficit-ridden operations; a growing state; continual self-inflicted crises originating from the public sector; zero accountability at any level irrespective of political ideology.

The fact that these conditions exist irrespective of political party of ideology is perhaps the greatest disappointment of all.

One can only hope that things will change.

Sources

This article was written in late September 2021. All data used comes from public sources. A list of these sources is provided here.

Cyprus GDP, Public Expenditure, Employment and Debt

All information was sourced from the CyStat website. For transparency, I am included my sources as well as my main datasets in addition to what has been published in the main article text.

Cyprus Statistical Service. 2021. Δημοσια Οικονομικα. ΕΣΟΛ 2010. (Public Finance, ESOL 2010). Last update 26/04/2021

Cyprus Statistical Service. 2021. Απασχοληση Στον Ευρυ Δημοσιο Τομεα: Τριμηνιαια Στοιχεια. (Employment in the wider Government Sector: Quarterly Bulletin). Last Update: 16/09/2021

Cyprus Statistical Service. 2021. Εθνικοι Λογαριασμοι – Κυριες Μεταβλητες. (National Accounts: Key Indicators). Last Update: 26/04/2021.

Other Sources

Aljazeera.com. 2021. Most Cyprus passports issued in investment scheme were ‘illegal’. [online] Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/16/half-of-cyprus-passports-in-cash-scheme-were-illegal-inquiry. [Accessed 24 September 2021].

Al Jazeera Investigations. 2020. The Cyprus Papers Undercover. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oj18cya_gvw. [Accessed 24 September 2021].

Cyprus Ministry of Finance. 2020. Draft Budgetary Plan 2021. [online] Available at: http://mof.gov.cy/assets/modules/wnp/articles/202010/757/docs/draft_budgetary_plan_2021_final.pdf. [Accessed 27September 2021].

Cyprus Ministry of Finance. 2019. Draft Budgetary Plan 2020. [online] Available at: <http://mof.gov.cy/assets/modules/wnp/articles/201910/504/docs/draft_budgetary_plan_2020_final2.pdf> [Accessed 27September 2021].

Cyprus Ministry of Finance. 2018. Draft Budgetary Plan 2019. [online] Available at: <http://mof.gov.cy/assets/modules/wnp/articles/201810/438/docs/draft_budgetary_plan_2019.pdf > [Accessed 27 September2021].

European Commission. 2019. Education and Training Monitor. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/et-monitor-report-2019-cyprus_en.pdf. [Accessed 26September 2021].

European Commission. 2019. The 2019 EU Justice Scoreboard. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. COM(2019) 198/2 [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/justice_scoreboard_2019_en.pdf. [Accessed 26 September 2021].

European Statistics Authority. 2021. People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by most frequent activity status (population aged 18 and over) [ilc_peps02]. Last update: 20.09.21. Extracted on: 21.09.21.

Heather Stewart, H. Smith. 2021. Cyprus forced to find extra €6bn for bailout, leaked analysis shows. The Guardian. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/apr/11/cyprus-bailout-leaked-debt-analysis-bill. [Accessed 25September 2021].

Hermesairports.com. 2021. Who We Are. [online] Available at: https://www.hermesairports.com/corporate/who-we-are. [Accessed 26 September 2021].

Manison, Leslie. Stockwatch. 2021. Παράθυρο στην Οικονομία. 2021. The Hellenic Bank-Cyprus Cooperative Bank Deal. [online] Available at: https://www.stockwatch.com.cy/el/blog/685933-hellenic-bank-cyprus-cooperative-bank-deal. [Accessed 27 September 2021].

Michele Kambas, S. Grey and S. Orphanides. 2021. Insight: Why did Cypriot banks keep buying Greek bonds?. Reuters. [online] U.S. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyprus-banks-investigation-insight-idUSBRE93T05820130430. [Accessed 26 September 2021].

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2018. PISA 2018 Results. Combined Executive Summaries. [online] Available at:https://www.oecd.org/pisa/Combined_Executive_Summaries_PISA_2018.pdf. [Accessed 24 September 2021].

Stockwatch. 2021. CS: Economic impact of explosion at €2.4bn. [online] Available at: https://www.stockwatch.com.cy/en/article/dimosionomika-oikonomia-energeia/cs-economic-impact-explosion-eu24bn.[Accessed 26 September 2021].

Wikipedia. 2021. Evangelos Florakis Naval Base explosion - Wikipedia. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evangelos_Florakis_Naval_Base_explosion. [Accessed 26 September 2021].

Wikipedia. 2021. 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis - Wikipedia. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2012–2013_Cypriot_financial_crisis. [Accessed 26 September 2021].